Blunt Force Trauma Lethality

The following is derived from a presentation to the January 2018 MAG Deadly Force Instructor class by Ed Vinyard, based on the December 2015 ACLDN article Understanding Blunt Force Trauma Lethality, An Interview with Dr. Robert Margulies by Gila Hayes and input from Dr. H. Anthony Semone and Dr. Ben Weger.

It’s critical for armed individuals, civilians and police alike, to understand the ability of even unarmed, untrained individuals to cause death or greivous bodily injury through blunt force trauma. Failing to control interactions early can leave you in a position where you’re left with no option but to use deadly force. Underestimating the capability of an unarmed opponent to cripple or kill — even the apparently small or weak — can leave you without the ability to respond at all.

Specific cases where fit and health people have been killed or crippled by unarmed, untrained, and physically unremarkable opponents are useful illustrations of the fragility of human life. My collegue John Daub has calalogued many such instances over the years. The knockout game may be the first example that comes to mind, and it’s certainly true that strikes to the head when completely unprepared are incredibly dangerous. But when there are signs ahead of time, maybe only seconds in advance, if you don’t actively protect yourself the warning alone is little help.

- In 2017, a 45 year old man was punched a single time while waiting in line outside a bar. His assailant first asked, “What are you looking at?” according to witnesses. The struck man never regained consciousness and died despite prompt hospitalization.

ABC 7 - In 2018 an off duty deputy involved in a minor traffic accident is punched once by the other driver, never regains conciousness, and later dies. KTLA, including video (start at 0:44)

However, even individuals who knew for certain they will be struck are at risk. Here are a couple examples where the person struck knew in advance that a punch was coming.

- In 2011, on a $5 bet, a 25-year old man was punched in the face by a 142 lb. woman. A few minutes later he collapsed; his autopsy revealed an artery burst in his neck. ABC news

- In 2014, two teenagers agreed to settle a dispute by allowing one to punch the other in the face. The teen, hit once on the left side of the face with a closed fist, fell, and struck his head on the ground. He never regained consciousness and died after hospitalization. Q13 Fox News

It might be tempting to write these anecdotes off as isolated incidents or freak occurances, but by understanding the mechanisms by which such injury and death occur, these tragedies can inform our own preparations for violence and its legal consequences.

For starters, consider moves illegal among unarmed boxers and MMA fighters because of the potential for death or permanent injury. Paring the list down to only moves that work via blunt force trauma still leaves a substantial selection.

- Groin strikes

- Punches to the back of the head

- Headbutting

- “12-6” elbows

- Kicks, knees, stomps to the head of a grounded opponent

Even with a “simple” punch to the head, there are a wide variety of mechanisms available that cause serious immediate or near-term consequences:

- Nose bone driven into brain

- Dislocated spine via blow to the top of spine or back of head

- Temporal artery tear via blow to the temple area

- Difficult to stop bleeding of spongy tissue (liver, spleen) via blow to the ribs

- Concussion due rapid twisting of unstabilized head (e.g., due to hook or “haymaker” punch)

- Cardiac contusion

Often, blunt force trauma causes secondary injuries such as

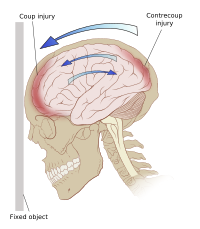

- Brain impacting front, then back, of skull (contrecoup)

- Head striking the ground for a second round of injury,

- Airway blockages due to bleeding and swelling from primary injury, and aspiration of blood and/or vomit

Past 40 years of age, the brain shrinks and there’s more room for the brain to “float” (and gain momentum) within the vault of the skull, so the danger of brain injury increases despite a person’s overt level of physical fitness.

There are injuries that, while not necessarily deadly, frequently lead to temporary incapacitation, which means the recipient of such an injury loses the ability to observe the aggressor(s) (e.g., reaching for a weapon) and respond in an organized way. If you carry deadly weapons on your person — a handgun or a knife — you’ve ceded control of those tools to your attacker if you lose the ability to retain them:

- Shattered testicle

- Kidney punch

- Temporary blindness due to blow to the back of the head

- Tearing due to blow to the nose

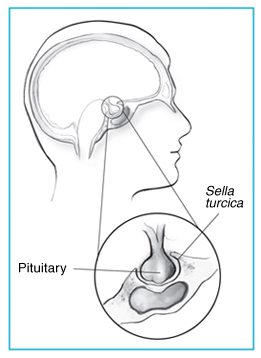

Finally, some of the life-altering connsequences of brain injuries can take months or years to surface as we’ve witnessed with boxers and football players suffering concussions. It’s not necessary to receive repeated concussions for bad effects. The pituary gland rests in a small cavity of bone the (sella turcica), and suffers the same kind of impact (coup and contrecoup) the brain does, which can result in long lasting effects that are difficult to diagnose and challenging to treat.

After we have faced the violence itself, our ability to clearly articulate to a jury what behavior required us to employ force can mitigate the sometimes-hostile legal environment we find ourselves. Even for the long-time student of self-defense, the bias can be surprising. During the closig arguments of Wyoming v Drennan, the prosecutor’s (false) claim that “in the state of Wyoming, there is a law against shooting an unarmed man” may have been among the open avenues for appeal, but it resulted in an initial conviction. While eventually prevailing at appeal is not the worst possible outcome, it is far from the best: that the jury be educated by our documented training, fully apprehending the dangers as we did.

“the legislature did not

intend that a hand could

be a dangerous weapon”

540 P.2d 394 (1975)

In Oregon v Weir, the supreme court of Oregon state deduced based on the structure of the penal code (Oregon’s three degrees of assault), that “the legislature did not intend that a hand could be a dangerous weapon,” despite also acknowledging that “if the other elements of assault were established, as a factual matter it would seem that the human hand could always be a dangerous weapon even the proverbial 98-pound weakling could, with one well-placed punch, disfigure a heavyweight boxing champion.”

As we’ve seen, it is just so.

None of this information is intended to suggest that we spend our lives in mortal fear of every other person around us. Rather seek out training and education that improve your ability to understand your own physical and legal context.

Here are four concrete steps you can take:

- Recognize pre-assaultive behavior or cues. Watch video and learn in a practical context such as Craig Douglas’ Managing Unknown Contacts course or one of KR Training’s force-on-force scenarios classes.

- Respond with well-developed counters. InSights Training’s

Street and Vehicle Tactics or KR Training’s Personal Tactics Skills. - Understand both the statutes and case law by which uses of force are judged in our state (or states we travel to). Look for courses like MAG-20 Classroom and Andrew Branca’s Law of Self Defense seminar.

- Document your knowledge of the danger presented by an unarmed assailant. Keep notes about videos you watched, articles or books you read, and training you receive. If you ever have to use force to defend yourself, make the specifics of what you knew

at that moment in time available to your defense attorney and the jury.