Over the past year I’ve been developing a new course for KR Training, Historical Handgun, that teaches the history & evolution of defensive handgun skills. Part of that effort has been seeking out and reading old books on shooting, purchasing copies signed by the authors when possible.

In 1935, WW1 veteran William Reichenbach published a book on bullseye shooting called “The Elusive Ten”. In 1936, he updated the book, re-titled “Sixguns and Bullseyes”, following up with “Automatic Pistol Marksmanship” in 1937. The Sixguns book was reprinted in 1943, but the other book was lost to history until it was reprinted, along with Sixguns and Bullseyes, as part of the NRA Firearms Classics Library, in 1996. (Another list of books published in this series is here.)

Reichenbach’s writing style is very informal and light. This sample of his description of trigger press, from The Elusive Ten (which you can read online for free), is a good example.

Reichenbach’s writing style is very informal and light. This sample of his description of trigger press, from The Elusive Ten (which you can read online for free), is a good example.

Sixguns and Bullseyes Highlights

In the first chapter, the author explains that the book is for new and aspiring bullseye shooters seeking to improve. He focuses on .22 rimfire and .38 special centerfire revolvers, primarily the Colt and S&W models.

He extols the virtues of the 0.100″ wide, red front sight — essentially the same kind of narrow, bright front sight used by modern competition shooters. The value of the narrow front sight has been known since the 1930’s — yet the factory front sights on almost all pistols are 0.125″, wide enough to fill the rear notch.

As common in many books from this era, he recommends a light grip on the pistol, because it “tires you less”. Modern courses of fire are timed in seconds and hundredths of seconds; bullseye occurs at much slower pace.

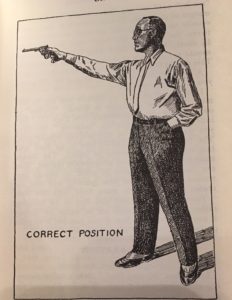

Similarly, his advice on stance is very relaxed, with non-firing hand resting comfortably in his dress pants pocket, and advocates shooting with both eyes open.

He provides the advice shooting instructors have been giving students since the dawn of gunpowder:

Practice as often as you can! Maybe, you do not have the facilities for shooting on a range each day — Not at all necessary! You don’t need a range for your short daily work-out! Any room will do. You practice “dry” with dummy shells! Stick a black paster up on the wall, at the height of your eyes, stand back and go through the motions. When the hammer clicks keep your bead and *call* your imaginary shots just as honestly as the real target would.

The concept of a small amount of daily dry practice producing great results is not new, although we seem to have re-discover it, or have someone of our generation be its champion for the idea to be widely accepted.

He plants the seed of an idea that grew up to be Comstock scoring used in USPSA competition:

My suggestion for competition would be: gun in holster. Upon command the gun should be drawn and fired once, the shot to hit a rather small target. The gun should then be re-cocked quickly and held up again at “ready” position, aimed at the same target. The whole action should be timed and the results judged by “time elapsed” and “value of hit”, the weight of scoring to lie with “time elapsed”.

His concept of a “full live fire practice day” is 3 strings of 20 shots each.

Some interesting drawings discussing gun fit for revolver stocks.

Automatic Pistol Marksmanship Highlights

The second book is all about semi-automatic pistols, which he refers to as “automatics”.

The book opens with his definition of two safety rules:

- An Automatic is Always Loaded!

- Never point the damn thing at anything you don’t want to hit!

These two rules may have been an influence on Col. Jeff Cooper’s development of his “4 rules“.

Even in 1937, the 9mm vs. .45 debate was common:

Just because a few Moros had been tickled with some .38 Revolver shells and had the audacity to survive, the .45 caliber craze became the credo. And “Shocking power” assumed such importance that it makes one sick. Less extremely large calibers do more effective work than the .45 calibre. It all boils down to the question of how good the shooter behind the gun is, and I claim that a calibre unnecessarily larger is not conducive to good handling.

Reichenbach was a big fan of the .38 super cartridge and preferred it to .45 ACP.

The combination of no hearing protection and one handed shooting made training with the 1911 .45 more difficult, as he notes:

There will never be an opportunity for fast firing in any situation, unless it be for the sake of noise or deception. Ordinarily, after the shooter has fired a .45 Automatic, say 10 times, he is all rattled..shaken up. Co-ordination is destroyed and he goes to pieces. To fire 50 shots with the .45 Auto, under target conditions, is an ordeal.

Despite this, Reichenbach preferred the Automatic as his daily carry gun:

I have developed an arrangement of gun and holster that suits me perfectly. My chest is thrown bravely forward. My eyes are serene and my mind is at ease. I know that I have a little steel-thing with me that carries death if need be, death to the enemy. I feel the instrument of utter security along with my waistband, and..alack, sometimes also a wee bit of weariness. The damn thing doesn’t weigh much, but it keeps it up–all day long. My tailor also objects to it because, he claims, he can’t get the perfect which which he so desires.

He describes the perfect automatic as one that

weighs 30 ounces, with distinct muzzle heaviness and a scientifically shaped grip, with the center of mass well forward and not near the handle. The insertion of the magazine should not materially shift the weight so far back that the gun becomes butt heavy.

Interestingly enough, the Glock 19 weighs 30 ounces, loaded, and has many of these characteristics, as do most of the modern 9mm polymer, striker fired pistols.

His preferred holster is an appendix/cross draw rig with the gun angled, and trigger guard exposed.

From later discussion, it appears that he carries hammer down on a loaded chamber, and intends to thumb cock the gun as part of the draw. (Those that followed him down the trail of defensive shooting eventually figured out that exposed trigger guard and thumb cocking during the draw were bad and dangerous ideas.)

The last part of his book on Automatics is all about what he calls “Practical Shooting“, which he defines as “the ability to draw our gun quickly, align it with speed and discharge it without pulling (flinching), at the target.” His description of how to learn a proper drawstroke should sound familiar to anyone that’s taken a defensive pistol course:

The last part of his book on Automatics is all about what he calls “Practical Shooting“, which he defines as “the ability to draw our gun quickly, align it with speed and discharge it without pulling (flinching), at the target.” His description of how to learn a proper drawstroke should sound familiar to anyone that’s taken a defensive pistol course:

Stand before a full size mirror. The hand goes down to the gun, takes it out of the holster, cocks and carries it to arms length. The bead is at the nose of our adversary. We squeeze the trigger! The whole action may take us fully 3 seconds. That’s fast enough for beginning. The thing is to see that the action is carried smoothly. There should be one deliberate, clean motion. Start right by starting with the slow draw. Work from the “Three Second Draw” to the “Two Second Draw” to the “One Second Draw”. I consider a draw executed with 1/2 second a damn fast draw. Whatever you do, make it your business never to miss your target! Never fire more than 50 shots a day. How about using a 5″ bullseye? If you get to the point you can hit a 5″ bullseye at 25 feet (8.3 yards) with a one second draw, you are a deadly shot and no fooling!

(By modern standards, hitting a 5″ target at 25 feet with a 1.0 second draw is USPSA Master/Grand Master level shooting.)

As with other books on pistol shooting from the 1930’s, the book is full of information that really hasn’t changed, and standards for “what is good shooting” that remain challenging today with modern equipment.

If this sort of thing interests you, I’ll be offering 1/2 and 1 day sessions of my Historical Handgun course August and September 2017, with additional sessions to be presented at the 2018 Rangemaster Tactical Conference and other locations to be announced soon. The course is mobile and can be presented in 1 or 2 day format at your location, if you have a classroom and a 50 yard range.

Pingback: KR Training July 2017 newsletter – Notes from KR

Pingback: Weekend Knowledge Dump- July 28, 2017 | Active Response Training