Over the past year I’ve been developing a new course for KR Training, Historical Handgun, that teaches the history & evolution of defensive handgun skills. Part of that effort has been seeking out and reading old books on shooting, purchasing copies signed by the authors when possible.

The Service Revolver and How to Use It – Captain C.D. Tracy (1917)

The author wrote the book during World War One, explaining:

The author wrote the book during World War One, explaining:

During the early stages of the War, the casualties which occurred amongst officers, both in trenches and in billets, through careless and uninstructed handling of revolvers, were numerous, if not altogether surprising, and strongly emphasized the need of correct training.

It’s the oldest book on handgun shooting I’ve found so far in my Historical Handgun work. It was scanned and restored in e-book format, and is available (free) from Lulu.com at this link.

Revolver vs. Automatic Pistol

Tracy makes the standard arguments, pro and con, for revolver and semiauto. “Revolvers are more reliable” (except that semiauto pistols have been rigorously tested and are reliable enough for law enforcement and military duty use, as well as self defense). Semi-auto pistols (aka “automatics”) have higher capacity and are faster to reload. Tracy was not a fan of small caliber pistols.

I saw an officer of ours fire five or six shots at a big Boche, but they didn’t stop him. He merely coughed each time he was struck by one of those bullets and came on again. Of course he was blood mad. He got to the officer and killed him with the bayonet. The officer was using a small automatic pistol, a .380 or a .320, I know the type as I have tried them.

During a political rising in South America, I was shot at close quarters, when mounted. My opponent was also mounted and we fired point blank. His bullet—a small copper one, .25 calibre, I think—passed right through my left lung and also passed through some of the fleshy part of my heart. I got my man in the chest and, as far as I know, killed him, as I was using a revolver similar to the Colt. His shot did not stop me, for I rode on and took part in the affray for some twenty minutes afterwards, when I dropped. The bullet remained in me for three days. It was then extracted from the back. After two winters in France in this War, I am still carrying on. I owe my life to my opponent using such a small pistol.

An officer of the Canadian Forces, an expert shot, armed with an automatic pistol in each hand, went into an enemy dug-out and encountered five men in it. Both pistols failed to act! He was shot, bayoneted, and left for dead. Later he dragged himself out and received further wounds from a bomb, losing both legs. Had this officer been armed with revolvers he would have undoubtedly made quick and short work of the enemy. An expert under such conditions would probably down all five of his opponents in less than so many seconds.

War Standards

Tracy defines some shooting standards. A good shooter should be able to put a shot into a 16×12 rectangle in one second (starting from ready), at a range of 10 yards. He does not specify whether the shooting is done from the hip or at eye level, using the sights or not.

For the revolver, he advocates shooting all shots single action, with cocking and firing done by firing hand. He advocates equal proficiency with both right and left handed (one handed) shooting.

Other standards: Six shots in 12 seconds (moderate), 6 in 6 seconds (expert)

Tracy suggests that most shots should be fired at distances from 5-20 yards. Shot cadence of once per second, can cock each shot. In this area, Tracy was far ahead of his time, as 5-20 yard aimed rapid fire was nearly forgotten until the 1950s, with most qualification courses focused on bullseye shooting at 25 and 50 yards and hip shooting at 7 yards or less.

Speed shooting drills:

6 shots, 5 yards, 1 second, 4” group (double action)

6 shots, 10 yards, 2.5 seconds, 8” group (single action)

Gear and Grip

Tracy recommends a 6” barrel length as ideal for active service, but observes that a 4” is handy in close quarters, easy to carry. He recommends a white metal or white tipped “foresight” (the UK term for front sight). The importance of a high contrast, easy to see front sight was known 100 years ago.

Pointing (Eyes, Stance, and Training generally)

Tracy discusses identifying the dominant eye, and the idea of developing natural point of aim using pistol barrel as a sight at close distances. Jim Cirillo would bring that idea back into the training community in the last part of the 20th century.

He recommends starting by having the student point their finger at the instructor’s eye from 8 yards away. This allows the instructor to see ‘backward’ down the student’s eye-target line.

Tracy then recommends that the instructor move to 5 yards, and let the student aim unloaded gun at instructor’s eye. While this violates modern standards of gun safety rules, a similar exercise could be done with a ‘red gun’ or any non-firing firearm replica that has sights. The only time I saw this technique used in a class was a course with former Gunsite instructor Jim Crews that I hosted in the 1990s.

For his presentation from a ready position, Tracy teaches a straight arm pistol raise, no bending of wrist or slackening of muscles. Like many in the early era of handgunning, he seems overly concerned with foot position, providing a diagram.

One odd piece of advice from his book: he suggests tightening the entire grip hard while pressing the trigger. Modern thinking is that the hard grip does already be at maximum pressure before any movement of the trigger begins. Generally moving any finger other than the trigger finger while firing a shot leads to unwanted gun movement and shots off target.

Tracy discusses the differences between “Snap shooting” (shooting with “some sense of direction”) and “Deliberate aim”, topics that would be mostly forgotten during the Jelly Bryce-influenced hip-shooter era, and re-discovered/popularized by Jeff Cooper as the ‘flash sight picture” years later.

Tracy notes: Though fear of recoil is supposed by many to be the cause of flinching, more probably the nerve-jar occasioned by the sharp report of the pistol is the main actual cause. Hearing protectors for shooting existed back in 1918. He names two brands: “Mallock Armstrong” and “Elliots”. Again, he was far ahead of his time in recommending their use in training. To correct flinching, he recommended ball and dummy drills and use of .22 ammo.

Loading the Webley

Tracy’s preferred handgun was the Webley revolver. Anyone interested in the specifics of that gun will find this book valuable and interesting.

1918 tactical target

Tracy’s concept of a tactical handgun target.

To stop a determined opponent actually in his tracks, when very close and almost making his point with his bayonet, two shots should be fired as quickly as possible.

To stop a determined opponent actually in his tracks, when very close and almost making his point with his bayonet, two shots should be fired as quickly as possible.

In most practices figure targets are used, and it should be borne in mind by the firer that such targets represent opponents who can, and will, hit first or hit back if not quickly and properly put out of action.

Revolver Shooting

Two handed revolver grip, circa 1918.

The double action trigger pressure must be started well before the pistol comes to the target, and its completion timed to occur at the same instant that the barrel is brought into alignment on the mark.

When firing rapid consecutive shots on several targets, it is very important to release the trigger smartly on the fall of the hammer, and instantly re-start the trigger pressure as the pistol is moving to the next mark.

Moving target

When firing at traversing or crossing targets, the cocking action should be employed. The pistol must be kept moving in the direction the target is going, and not stopped at the moment of firing. The arm and upper part of the firer’s body should be kept rigid, the movement being from the waist.

At ranges of 15 to 25 yards, aim should be taken on the front edge of the running man target, and at his waist line. At shorter ranges, say 8 to 10 yards, aim may be taken about four inches further back on the target. With some practice, the moderate shot should score a high percentage of hits on a running man target crossing at a “five minute gait” that is, at about 12 miles an hour.

Not until the firer becomes fairly expert in his practice at the shorter range should he attempt the longer.

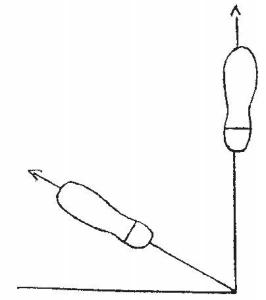

How to draw, 1918

Hook the three fingers under the butt, and lift the gun with the trigger finger extended outside the trigger guard. Swing the muzzle forward to the mark, at the same time slipping the trigger finger on to the trigger, and using the trigger action, so that the hammer falls forward at the exact instant the barrel is directed to the mark. In the early stages of practice, it should not take more than one second to bring the pistol into action in this way.

Texas men were noted for their speed on the draw. Some of them wore the holster very low on the thigh, and tied to the leg by a small strip of raw hide, passed through the muzzle end of the holster.

The pistol was fired by the “throw”—that is, drawn with an upward swing on the muzzle, the hammer pulled back and held by the thumb, the pistol then instantly brought down and forward to the mark, being checked with a jerk, thus freeing the hammer at the moment the barrel reached the desired downward and forward throw. The jerk freed the hammer from under the thumb, thus causing the discharge.

Doors

In tackling a dug-out, or house, a man should never stand directly in front of a door when there is the possibility of hostile reception. If possible he should get on one side of it, free the latch, and kick the door suddenly and violently open, commanding the room in sectors, exposing only his pistol hand and eye round the door-post.

Use of Cover

Tracy shows correct use of cover

as well as the wrong (no) use of cover.

DUAL WIELDING

With a little practice it is possible at close quarters to fire effective shots simultaneously from two revolvers at two separate objects not very far apart. The writer finds that this can be done by fixing the gaze on a spot at a point half-way between the two objects.

The fact is easily proved in the following way;—Get two people to verify your aim by standing about ten feet apart and facing you, at a distance of 15 to 20 feet. Glance at the left eye of the man to your left, and at the right eye of the man to your right, and then at a spot midway between the two people, level with their eyes. Keep your gaze on this central spot, fully extend each arm, pointing with index fingers, or two unloaded revolvers, at the two original aiming points (viz., the men’s eyes). This method has its value when “holding up” or taking a number of prisoners and preventing or dealing with a return to hostilities on their part.

SUMMARY

Overall, Tracy’s book was far ahead of its time, introducing concepts and standards for drills that would be largely ignored or forgotten until the 1960s in the Jeff Cooper era. With very few exceptions the content of the book is still relevant and correct by modern standards.

Pingback: KR Training February 2018 newsletter – Notes from KR

Pingback: Target Evolution: B-21, B-21X, to B-27 and beyond – Notes from KR

Pingback: Weekend Knowledge Dump- March 2, 2018 | Active Response Training